If you used sub-menu on the Mac and did the same thing on Windows, you probably have noticed they behave somewhat differently between these platforms.

In both cases, there is a delay before the sub-menu opens. This is useful because it prevents sub-menus from opening when you move your cursor to the bottom of the parent menu. But the longer the delay, the longer you have to wait hover the parent menu item before the sub-menu opens. This delay is shorter on the Mac.

In both case there is also a delay before the sub-menu closes. This delay is counted from when the pointer exit sub-menu title’s in the parent menu to go on one of it’s neighbors items. Both platforms use a delay of about one second, but there are exceptions that can cause the sub-menu to close before the end of the delay. On Windows, it’s a click on another element of the parent menu. On the Mac, it’s a little more complex than that…

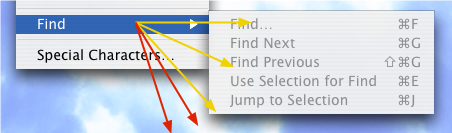

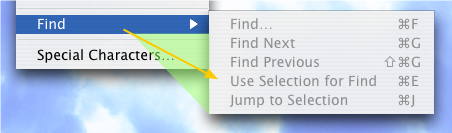

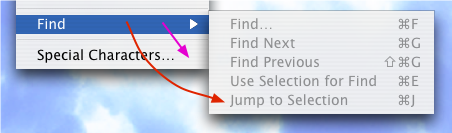

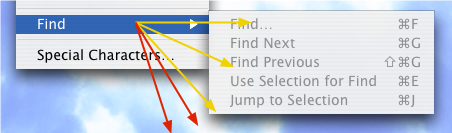

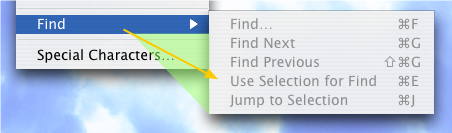

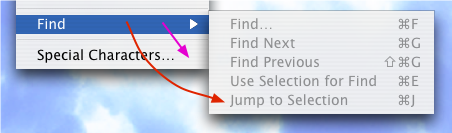

The arrows on the above picture show different pointer movements. If you do on the Mac the move from one of the yellow arrow, the sub-menu will stay on-screen — as long as you reach the sub-menu within the one-second delay. On the other hand, if you move your mouse according to one of the red arrows, the sub-menu will close immediately when the pointer exit the “Find” item from the parent menu.

Another difference from the Windows menu behaviour is that no other item from the parent menu get highlighted when the sub-menu is open. When the pointer follows the path of one of the yellow arrow, the “Special characters…” item never highlight, even if the pointer moves over it, as long as the sub-menu stays open. This may seems strange at first, but things could get confusing for a moment otherwise. Imagine that “Special characters…” contains also a sub-menu, how can you know which one of the sub-menus is displayed at a given time? You have to wait one second to be sure that the displayed sub-menu match with the displayed one.

How does it work? It’s simple: as soon as the pointer leaves the parent element in the menu, a triangular region between the current pointer position and the sub-menu bottom corner is defined. If the pointer leaves this region, sub-menu closes immediately. If not, the user has about 1 second to move the pointer inside the triangle, after that, if the cursor is still not in the sub-menu, the sub-menu closes.

This approach has some drawbacks. First, it is impossible to move to the sub-menu using a curve like shown by the red arrow on the previous image, because this means the pointer has to leave the “safe” triangle.

Also, if we move the pointer so that it stays in the region, but stop in the middle to select the next element in the parent menu, we must wait the end of the one second delay before it becomes highlighted. This is particularly annoying when a sub-menu is very long, making the triangular region bigger.